This week we have reached Richardson’s novel Pamela, or virtue rewarded, the sole novel on this course’s reading list. For those who have not gone through the reading experience themselves, we will first introduce you shortly to the main narrative and the most important themes in this novel. A few key elements will be more elaborately discussed further and we hope we can convince every one of the novel’s highly dubious status concerning its moral.

This week we have reached Richardson’s novel Pamela, or virtue rewarded, the sole novel on this course’s reading list. For those who have not gone through the reading experience themselves, we will first introduce you shortly to the main narrative and the most important themes in this novel. A few key elements will be more elaborately discussed further and we hope we can convince every one of the novel’s highly dubious status concerning its moral.

The protagonist of Pamela, or virtue rewarded is Pamela, a fifteen year old servant who shares her life-story through letters and diary entries. The main narrative deals with Mr B who tries to seduce Pamela, but she shows determination to refuse him. The novel is correctional and Mr B evolves to finally propose marriage to Pamela, thus having gained an interest in both her mind and body, rather than merely her body. Pamela then attempts to adapt to high society and builds up a successful relationship with her husband. There are a number of themes we can distinguish in the novel, the most important ones are love, virtue, money, gender and class distinctions.

Different notions of love are distinguished in this ‘love story’. Pamela engages in familial love towards her parents, in her letters and continuously throughout her writing. Sisterly love is found between Pamela and Mrs Jervis, who share a deep friendship. The false love of Mr B for Pamela finally transforms into true love hereby granting a ‘fairy-tale-ending’.

Pamela is above all very much concerned with the preservation of her virtue, which she keeps on repeating constantly. While Mr B wants to fulfil his ‘needs’, Pamela continues to refuse any offers of money or goods in exchange for sexual pleasures, therefore keeping herself virtuous. The moral of the novel would be that this virtuous behaviour turns out to be rewarded, since Mr B loves Pamela all the more for her consistency in the end.

The notion of money in the novel is very ambiguous. We most certainly link this to Mr B who tries to persuade Pamela to give up her virtue in return for money, clothes and jewellery, and furthermore bribes and manipulates everyone else around him. However, Pamela’s attitude towards money and material objects in general is not always straightforward.

Pamela is continuously stressing how poor her parents are which supposedly prides her. This sharply distinguishes her from her master, who is evidently better off. Between the two there is an enormous gap, since their class differences separate them. The gender difference complicates their relationship even further since Pamela is powerless in comparison to her master.

Preface: by the editor

The first two editions of Pamela were published anonymously. The title page stated Richardson to be the printer of the book – he was a successful printer and printed all his own novels – but the letters were supposedly found and edited by an anonymous editor. This contributed to the alleged authenticity of the letters as a “found manuscript” and constituted the figure of Pamela as a soap opera-like character that people could really identify with. Since she was put forward to be an example of good behaviour and virtue, it was necessary that as many readers as possible could identify with her. When Pamela was first published, however, it not only evoked a wave of admiration and swooning amongst its esteemed readers, it also inspired a series of parodies and what were, according to Samuel Richardson, misreadings of the novel. Richardson was unpleased to learn that part of his audience doubted Pamela’s good intentions, her sincerity and even her virtue. Highly upset about these interpretations of his work, Richardson edited the next editions of Pamela. He continuously attempted to guide the reader through the novel and control the conclusions that he thought should be drawn after reading this work. He added a preface that stated which moral values the reader should read into Pamela. He also enclosed a summary of the letters that the book consists of, stressing the main issues they touch upon.Additionally, he altered the manner of speech of the protagonist, Pamela, after having received comments that since she was to be an example for young ladies, she should speak and write in a way that was to be admired by everyone. All his attempts at controlling the readers’ interpretations were in vain: the interpretation of the novel remains a controversial topic today.

Epistles

Pamela’s letters serve as a catalyst to reform both the character of Mr B and the reader of the novel, who is supposed to evolve with Mr B as he reads them. Within the novel, these letters provide Pamela with a means to pour out her heart and seek the much-needed guidance of her parents. She uses her letters as a platform to record her true feelings and her version of the encounters between herself and her master. To Mr B the letters are items of both frustration and admiration. He increasingly values Pamela, who wrote the letters, but is at the same time slightly tormented by the fact that he cannot control what she writes. When she is imprisoned, the letters evolve into diary entries. This symbolises how she increasingly loses freedom and is therefore forced to rely upon herself as an authoritative figure more and more.

Pamela’s virtue revealed

Pamela was intended to function as a communal code of conduct or, at least, provide guidelines in terms of letter-writing. There seem to be a number of problems in Pamela’s behaviour that indicate multiple possible interpretations of the novel’s moral, therefore many works have been written as a response to Richardson’s. Some of the works inspired by Pamela were probabilistic sequels, whereas others gave proof of a mocking undertone. A well-known work in this respect is An Apology for the Life of Mrs Shamela Andrews, written by Henry Fielding. Shamela was published less than a year after Richardson’s Pamela and offers a satirical version of the latter. It represents the self-proclaimed real account of the events which took place in the novel by Richardson. Shamela, which is Pamela’s so-called real name, is said to be the actual seducer instead of Squire Booby, who represents the character of Mr B, such as is illustrated in the next section:

(…) ‘thank your Honour for your good Opinion,’ says I and then he took me by the Hand, and I pretended to be shy: ‘Laud,’ says I, ‘Sir, I hope you don’t intend to be rude’; ‘no’, says he, ‘my Dear’, and then he kissed me, ’till he took away my breath—-and I pretended to be Angry (…) [Fielding, eBook]

By rewriting Richardson’s novel, Fielding reveals his frustrations with the hypocrisy of the main female character. Pamela is represented as the very essence of chastity and humility, but as becomes clear in Shamela, her behaviour is nothing but false pretence. She projects a virtuous image of herself in order to seduce Squire Booby and climb the social ladder. In the introduction to Shamela, Fielding explains what inspired him to write a satire:

An apology for the life of Mrs Shamela Andrews. In which, the many notorious falsehoods and misrepresentations of a book called ‘Pamela’ are exposed and refuted; and all the matchless arts of that young politician, set in a true and just light. [Fielding, eBook]

Pamela repeatedly feels the need to express her pride in respect to her parents’ poverty and her own virtuousness. According to her, poor living conditions are to be preferred above selling one’s virtue to the highest bidder. What is strange, however, is the frequency at which she repeats this matter over and over. She regularly inserts people’s words of praise for herself and at times this comes across as presumptuous such as the section below, which originates from one of Pamela’s letters, illustrates:

She told me I was a pretty wench, and that every body gave me a very good character, and loved me; and bid me take care to keep the fellows at a distance; and said, that I might do, and be more valued for it, even by themselves. [Richardson, 12]

Another example of Pamela’s need to justify her actions and acquire praise for them occurs at the moment when she is allowed to leave the house of her late mistress. With her future life in mind, she divides her belongings into three piles. One pile is consecrated to gifts of her former mistress, a second one consists of the luxurious presents her master offered her and the final pile contains her own personal belongings. Almost dramatically Pamela declares that she cannot take any objects from the first two piles with her and strongly emphasizes to be proud of her poor origins. Despite her affirmed pride, she does take a few gifts with her for so-called practical reasons. The reason why Pamela does not take more presents with her seems to be her concern for what other people might think: ‘(…) for poor folks are envious as well as rich (…)’ [Richardson, 63].

Furthermore, Pamela proves to be very materialistic throughout the novel. She constantly stresses that here poor origins and low status are something to be proud of,

Furthermore, Pamela proves to be very materialistic throughout the novel. She constantly stresses that here poor origins and low status are something to be proud of,  it appears as if she needs to convince herself of that exactly. Her materialistic attitude is apparent in her behaviour regarding clothes and appearance in general. On all occasions Pamela tries her very best to wear the nicest clothes she thinks suitable for the occasion. Not only nowadays do we consider her interestin fine clothing to be not so virtuous and innocent at all, but Mr B implies that in those days her attitude was ambiguous too:

it appears as if she needs to convince herself of that exactly. Her materialistic attitude is apparent in her behaviour regarding clothes and appearance in general. On all occasions Pamela tries her very best to wear the nicest clothes she thinks suitable for the occasion. Not only nowadays do we consider her interestin fine clothing to be not so virtuous and innocent at all, but Mr B implies that in those days her attitude was ambiguous too:

‘who is it you put your tricks upon? I was resolved never to honour you again with my notice; and so you must disguise yourself, to attract me, and yet pretend, like an [sic] hypocrite as you are-’ ‘I beseech you sir,’ said I, ‘do not impute disguise and hypocrisy to me. I have put on no disguise.’ ‘What a plague’ said he, for that was his word, ‘do you mean then by this dress?’ [Richardson, 90].

The main cause of Pamela’s virtuous behaviour is her Christian upbringing. God appears to be the only higher power to which she submits. Pamela claims that her main concern is to remain chaste, so that her soul would not be lost. She resolutely wards off Mr B.’s impure intentions, which ultimately results in him asking for her hand in marriage. However, as indicated there are some serious flaws in Pamela’s behaviour that clash with religious ideals.

conclusion

The moral lesson to be deduced seems to be that chaste behaviour leads to a marriage with a wealthy man. Pamela’s virtue is rewarded, because her master realises the errors of his ways after reading her letters and starts developing romantic feelings for her instead of mere lust. Nevertheless, the implied guidelines are far from those in Christian faith. In Pamela the ultimate achievement seems to be a beneficial marriage, whereas, in terms of religion, it would be to obtain a place in heaven. Therefore it could be said that the intended morality of the story is somewhat overshadowed by a materialistic fairy-tale-style ending, like Cinderella but with a touch of Beauty and the Beast. Another anti-Christian element in Pamela is to be found in a not always subtle sexual undertone. The sole purpose of Mr B.’s flirtatious actions towards his servant is to lure her into profligate behaviour and despite the didactic purpose of inserting such behaviour, its presence would be disapproved of by religious standards. According to Christianity, the body is to be erased until marriage, after which sexuality should solely serve as a means to procreation. To make matters worse, Pamela seems to be highly concerned with wearing fine clothes in order to please her master, whom she still occasionally compliments despite his initial vile behaviour. In short, the intended morality in Pamela is at times ambiguous, because the authority of Pamela as an example for virtue is repeatedly undermined. The faith she invests in God is not represented in her strong wish to be accepted by members of the higher social classes, nor in her materialistic tendencies.

Sources:

Fielding, Henry. An apology for the life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews: In which, the many notorious falsehoods and misrepresentations [sic] of a book called Pamela, are exposed and refuted; and all the matchless arts of that young politician, set in a true … light. …Oxford: Printed for A. Dodd, 1741. Print. digitalized: 3 Oct. 2007.

Hammerschmidt, Sören. “Week 11 The Media Event.” Ghent University. Auditorium M, Rozier. 5 Dec. 2012. Lecture.

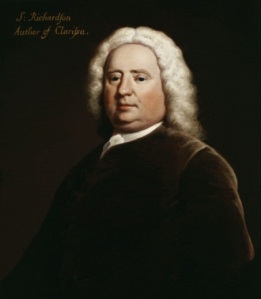

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Samuel_Richardson_by_Joseph_Highmore.jpg

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00775dh

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks?gid=65649%21&ws=acno&wv=list

Richardson, Samuel. Pamela, or virtue rewarded. New York: Penguin, 1980. Print.