As a nine year old, William Blake claimed he saw a “tree filled with angels”, moreover, he never outgrew or denounced these visions. His favourite artists were those unappreciated in their time, such as Michelangelo. So it is rather obvious that William Blake was not one likely to conform to the norm. William Blake was a true artistic rebel, commenting on contemporary society and placing himself deliberately outside of the literary scene. In the eighteenth century, most authors had very little control of their works as they were printed and sold. William Blake, however, decided to create his own illustrations and print his own works, as a result he kept full control.

The process of creation followed by production was very important to Blake, bearing in mind that he created a concept, for which there had to be a balance between writing and illustrations. The entire work had to be his, as he envisioned a concept and not a mere book. His name on the frontispiece functioned as a signature, similar to a painter signing his work. He was printer and author, thus explicitly stating he was sole creator of this work. William Blake produced his books as a form of art, very luxurious pieces, they were not intended for the book market.

The fact that his books were not meant for the book market, is also made clear by how they were printed. The most economical method of printing at that time was typesetting, for which woodcuts were used. Ink was poured on top of the woodcuts, on the raised letters, then it was pressed on the paper. This form was mostly used by printers at that time. However, there was a different manner, which was more laborious. Copperplates were engraved with a design, poured over with ink and after the ink had been wiped off, it was pressed on paper. The indentations left their mark on the paper. Copperplate-printing enabled the printer to add a lot more detail.

William Blake even invented a new form of copperplate printing. He sought to improve the intaglio manner, in which the design was scratched onto a waxed surface before being engraved deeper or a needle was used to map it out into an acid-resistant coating before pouring acid onto the plate. Therefore, he came up with relief etching, whereby the design is painted onto the copperplate with acid-resistant varnish, leaving the unpainted surface to be eaten away and the rest in relief to be printed. Moreover, this had to be done in mirror image. So, it is clear that this was a very laborious process, which could not be done for mass production. Each page had to be etched separately into a copperplate, that lasted only for about 1000 copies. Therefore, Blake focused on producing individual copies for individual and rich patrons.

William Blake even invented a new form of copperplate printing. He sought to improve the intaglio manner, in which the design was scratched onto a waxed surface before being engraved deeper or a needle was used to map it out into an acid-resistant coating before pouring acid onto the plate. Therefore, he came up with relief etching, whereby the design is painted onto the copperplate with acid-resistant varnish, leaving the unpainted surface to be eaten away and the rest in relief to be printed. Moreover, this had to be done in mirror image. So, it is clear that this was a very laborious process, which could not be done for mass production. Each page had to be etched separately into a copperplate, that lasted only for about 1000 copies. Therefore, Blake focused on producing individual copies for individual and rich patrons.

Blake made the work even more laborious and time consuming by making extensive use of colours which had to be printed consecutively and separately. True to his nature of a media transcending artist mixing artist categories like painter, printer and poet (cf. supra), themes found within his poetic word sculpting in his poems also shine trough in each individually conceptualised and realised edition where the coloration is used as a supplementary tool to further the themes addressed by and in his works. Corroborating this is a comparison of differences between several editions of The songs of Innocence where coloration differences can be seen to signify the real world interplay between the major themes addressed within the work.

Where the French Revolution was first hailed by British poets, this quickly shifted after the rise of Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins in France, where the so called Reign of Terror was responsible for the mass killings of thousands. A reflection of this can be seen in editions realised around that time where first, in line with the positive way the revolution was seen, bright colours overflowed the title page. But when times changed and the French Revolution totally became synonymous with the Age of the Guillotine and all ideals seemed to be unrealised, dark colours start taking over the title page.

As a true multidisciplinary Blake takes to heart a role frequently envisioned by poets and other artists alike; not solely portraying and representing but by their works alerting people to the world around them.

Importance of Blake’s illustrations for specific poems

The Clod and the Pebble

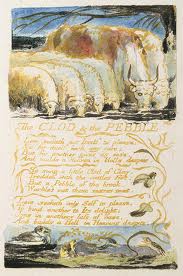

“The Clod and the Pebble”, a poem from Songs of Experience, is not part of an obvious pair of poems. Moreover, it seems to incorporate both innocence and experience, and demonstrates Blake’s typical contrasting values in one poem.

At first the poem seems to balance both points of view, as the clod and the pebble get an equal amount of lines to express their opinion. The word “but” in line 6 is the turning point from the Clod’s argument to that of the Pebble. The clod expresses an argument of innocence, while the pebble utters a more experienced view. The fact that Blake selects the latter to end the debate with may show his tendency to lean towards favoring that argument, but he may just as well be respecting the chronology (first innocence, then experience – within the different versions of these books, poems sometimes were moved around). However, as both concluding lines of the arguments seem rather balanced, he is as well forcing the reader to make up his own mind.

At the same time, Blake was not just giving textual clues, but visual clues as well. Since Blake was responsible for the engravings illuminating his poems, he could easily “guide” the reader to one opinion or another trough, for instance, meticulous selection of the colours used.

As for the imagery illustrating this poem, it is the environment in which the clod and the pebble find themselves which is depicted here, the clod nor the pebble can be found. The fact that neither of them are shown could imply that they are merely representing abstract ideas.

Blake shows us quite a peaceful scenery, the cattle drinking, and the frogs playing in the brook. Even though the pebble utters quite pessimistic thoughts, there is no explicit visual show of a thread whatsoever.

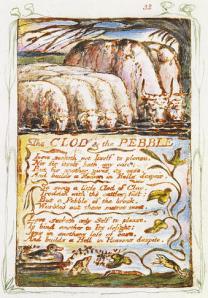

In other versions, the colours change, this is shown most explicitely in a 1795 version:

Only by changing towards more dark colours, the poem gets a much more gloomy feel to it, leaving the reader with the idea that, even though the stanzas are balanced, the pebble’s judgement is the one favoured by the author (in contrast to the 1794 version shown above, with its more lively and light colours, which seems to emphasize the clod’s opinion of love.)

Later versions, such as a 1825 version:

Once again show a more peaceful and balanced imagery. Blake constantly played around with the colours of his images, switching from light to dark and back, and as such adding more possible interpretations every time he finished another edition.

The Chimney Sweeper

In The Chimney Sweeper, Blake talks about little children –they were the only ones small enough- that had to sweep out chimneys. This sort of child labor was actually very common in 18th and 19th century England. The Chimney Sweeper in Songs of Innocence (1789) has a first person narration, the viewpoint is that of a little child sweeper. The ‘weep! weep! weep! weep!’ of the third line evokes a very strong sympathetic feeling with the narrator. “But just because the misery is so concretely realized, the affirmation of visionary joy is more triumphant than in any other poem of the series.” (E.D. Hirsch: 1964)

Blake is definitely a man of contrasts (already indicated in the subtitle: “Shewing the two contrary states of the human soul”) and his mastership in making them ‘work’ becomes apparent in this poem. The poem derives its Songs of Innocence copy B, 1789, 1794 (British Museum): genius and strength from the contrast between the woeful, horrible job in real life and the joyful bliss in the dream. It is the latter part that Blake focused on when he made the illustration that accompanies The Chimney Sweeper. Underneath the actual words one can see the ‘Angel’ figure (line 13) that is pulling a boy (probably ‘Tom Dacre’: line 5) from the earth (or ‘coffin’: line 14) and thus setting him free to go ‘down a green plain, leaping, laughing’. It is this dreamlike setting that fills the young boy with warmth when he has to get up in the morning. Although the child sweeper has a pitiful existence (his mother is dead and he has a horrible job), the poem is eventually one of hope; this feeling is definitely enhanced by the illustration.

The Chimney Sweeper from The Songs of Experience (1794) seems less hopeful. Here the narrator asks the sweep to tell him his story. So, again, most of the poem is told from the child’s point of view. Unlike in the previous poem, the mother here is still alive. Still, the child is all alone in the snow, because its parents “are up to the church to pray” (line 4). This scene of loneliness is brilliantly evoked by Blake’s illustration: one can see “A little black thing among the snow” (line 1) and apart from the snow and the houses, there’s no one else, the streets are completely deserted. The child, then, is all alone “to sing the notes of woe” (line 8).

This poem is, in our opinion, directed against the rigid hierarchy of the Anglican church: “God & his priest & King”(line 11) “make up a heaven of our misery”. The authoritative figures tell the less fortunate they have to grateful for the life God has given them, moreover, they ‘soothe’ the poor by explaining that they will achieve heaven if they work hard enough. The sweeper is, in fact, happy, but not because of the comforting lies the churchmen tells it: “what makes the sweep happy in his misery is not that sinister delusion, Heaven, but the strength of life that is in him.” (E.D. Hirsch: 1964). This is explained in the second stanza.

This poem is, in our opinion, directed against the rigid hierarchy of the Anglican church: “God & his priest & King”(line 11) “make up a heaven of our misery”. The authoritative figures tell the less fortunate they have to grateful for the life God has given them, moreover, they ‘soothe’ the poor by explaining that they will achieve heaven if they work hard enough. The sweeper is, in fact, happy, but not because of the comforting lies the churchmen tells it: “what makes the sweep happy in his misery is not that sinister delusion, Heaven, but the strength of life that is in him.” (E.D. Hirsch: 1964). This is explained in the second stanza.

Again, the illustration of the dirty, gritty sweeper full of soot with is mouth open, seemingly crying “weep, weep” (line 2) is an enhancement of the ideas formulated in the poem itself.

Hence, it is clear that “[t]o read a Blake poem without the pictures is to miss something important: Blake places words and images in a relationship that is sometimes mutually enlightening and sometimes turbulent, and that relationship is an aspect of the poem’s argument.” (Norton Anthology)

Bibliography:

Eaves, M. & Essick, R.N. & Viscomi, J. (2012) Works in the William Blake Archive. Viewed on 29/11/2012, http://www.blakearchive.org/blake/indexworks.htm?java=yes

Greenblatt, S. (2006) The Norton Anthology: English Literature Volume D. London: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Hagstrum, J.H. (1964). William Blake Poet and Painter. London: William Clowes and Sons.

Hirsch, E.D. (1964). Innocence and Experience: An Introduction to Blake. Clinton: The Colonial Press