What was English theatre like in the eighteenth century? How did it feel to be there – either on stage or as a member of the audience?

We, as a class, took the test and performed parts of Henry Fielding’s The Author’s Farce, just to get acquainted with the style, habits, and livelihood of a stage comedy.

Fielding & The Author’s Farce

Let us begin by introducing the playwright. Henry Fielding (1707-1754) was born at Sharpham Park, Somerset, and belonged to a wealthy and respected family. Though not an aristocrat himself, he was related to the Earl of Denbigh, and his mother belonged to a powerful family of lawyers. Fielding’s father sent him off to the prestigious Eton College, where he learned to appreciate the classics. In 1728, he went to Leiden, in the Netherlands, to study law and the classics. When he came back, he devoted himself to writing for the stage. His first two plays were performed at Drury Lane, one of London’s leading theatres at that time. Fielding wrote mostly comedies, some of which were very critical of the political and literary establishment. In particular the contemporary government of Sir Robert Walpole was the aim of a great deal of Fielding’s satire.

The year 1730 was of great success for Fielding. That year, he had four plays produced, among which we find The Author’s Farce, a farce “with a puppet-show, call’d the Pleasures of the Town.” Arguably, this play was Fielding’s first great success in the London theatres. That same year, another now famous work was staged: Tom Thumb. It is perhaps best known in the 1731 expanded version entitled The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great.

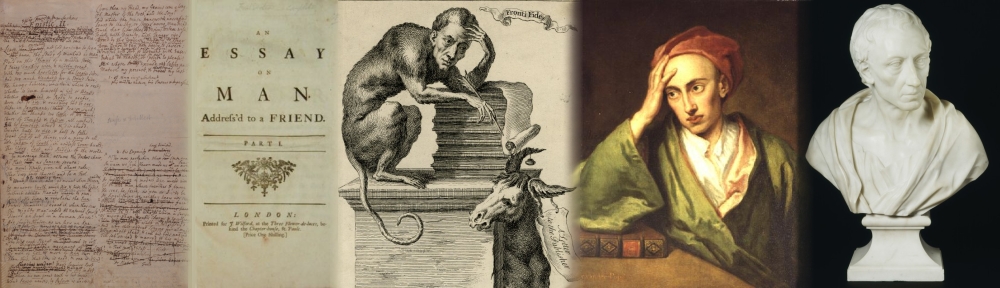

The front page of the printed version of The Author’s Farce

The front page of the printed version of The Author’s Farce

(as found on http://archive.org/details/authorsfarcewith00fiel)

Criticizing and laughing with the political establishment, of course, could not go on forever. The Walpole administration initiated the infamous Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737, probably in response to (primarily) Henry Fielding’s plays. Also John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera is often mentioned in this context. The play that triggered the act, however, was – we believe – not written by Fielding. The Golden Rump, as it was called, could even have been commissioned by Walpole himself, to give him a valid reason to institute censorship. Although we shall probably never know what happened, we know for certain that Fielding’s critical plays had set the tone. After the Act had been passed, all plays were censured and adapted (though implicit satirical messages were sometimes overlooked) before they could be staged in one of the only two ‘licensed’ playhouses, Drury Lane Theatre or Covent Garden Theatre (both called Theatre Royal later).

For a while, the playwright retired from the theatre and began working as a barrister. However, he never stopped writing satirical pieces for newspapers and in letters. Nowadays, Henry Fielding is also well known for his novels. The first of these, Shamela, was triggered by Samuel Richardson’s scandalously popular novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. Both were written in the epistolary form, but Shamela was of course harshly satirical in nature. The novel was then followed by Joseph Andrews (1742) and several other novels. Fielding’s number-one success was The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (1749), a foundling’s tale discovered on the property of a very wealthy, benevolent landowner.

Not only was Fielding a successful author and playwright, he also had a notable career in law and order. Thanks to a political appointment, he became Chief Magistrate for London. He also founded the ‘Bow Street Runners’, London’s first professional police force.

Eighteenth-Century Theatre

When we read a printed play dating from the eighteenth century, it is hard to imagine how the actual performance may have looked like. From written sources dealing with the theatre at the time, we know that performing or watching a play was certainly very different from what we are used to nowadays. To get an idea of just how different it was, we travelled back in time to the old era in our “English literature: literary texts of the eighteenth century” class. In our lecture theatre, we staged the first few scenes of Henry Fielding’s The Author’s Farce (viewable here) in an attempt to reconstruct an eighteenth-century performance as a whole, certain characteristics of which would bewilder most twenty-first-century theatre-goers.

As for going to the theatre in the eighteenth century, the most crucial difference is that this, as opposed to nowadays, was primarily a social event. Therefore, audience members were not quietly sitting in a chair in a dark theatre, attentively watching the play. The actors had to fight to captivate the noisy audience. Illustrative is the fact that the whole theatre was equally lit, signalling that there was no rigid boundary between actors and audience, and that both were considered equally important.

A performance of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera; here, it can be seen

A performance of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera; here, it can be seen

that wealthier people could buy their seats on the stage itself.

(as found on http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/0-9/18th-century-theatre/)

Spectators were walking around during the play, chatting with friends or even talking to the actors. Wealthy audience members could sit on stage and display their status by giving clever remarks, talking with actors or actresses, and showing off their nice clothing. As became clear during our class performance, the ‘interactive audience‘ situation could easily culminate in anarchy, especially if the play was not appreciated. Audience members would shout critique or insults, or even throw things at the actors. Actor Edward Cape Everard draws the line at potatoes: “Our situation on the stage, from being often rendered unpleasant, was sometimes dangerous; apples and oranges we got pretty well used to from their frequency of appearing; but when our unthinking spectators would sometimes salute us with a potatoe, or even a pint or quart bottle, it was above a joke.” (Memoirs of an unfortunate son of Thespis, Edinburgh 1818, p. 104).

There was also always more than just a play on these social nights. Other forms of entertainment were offered on the side. The play would be preceded by a musical performance and there was generally an interlude during which a great variety of entertainment could be offered, from songs to dog tricks. Finally, the night would be closed by a musical performance. Audience members also ate and drank during the play, hence the flying apples and pint bottles. So-called orange wenches – a role played by our very own professor Hammerschmidt during the class performance – walked through the theatre and provided the audience with fruit, and often also other services (‘orange wench’ soon became a euphemism for prostitute).

Theatre-going might have been a very different experience in the eighteenth century, other theatre-related phenomena which started around that time seem much more familiar to twenty-first-century audiences. Like with our contemporary Hollywood films, the entertainment did not stop at the theatre walls. Next to the actual theatre performance, which was accessible for a very wide range of people, there were of course also printed versions of the play, mainly bought by richer people. These scripts were usually bought as a collection of loose sheets, but these could be bound as well.

A new phenomenon at that time was that certain actors became stars. They were not only helping to promote a play, but they also gave rise to merchandising: fans could buy porcelain statues, portraits, engravings and other products. One of the most popular stars of the eighteenth-century theatre was David Garrick, who was among the first to adopt a less affected, more natural acting style. Furthermore, costumes were introduced in Garrick’s days; previously, actors wore contemporary (i.e. eighteenth-century) clothing.

A tea caddy featuring David Garrick

A tea caddy featuring David Garrick

(as found on http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/0-9/18th-century-theatre/)

To conclude this post on eighteenth-century theatre, we can only advise you to watch the video made in class, as it will hopefully enable you to understand how the staging of a play in playhouse actually may have been like. Most of the elements summed up above are included in this performance (or, in any case, an attempt was made to do so), and all of these make the video worth watching, especially in combination with the actual staging of Fielding’s The Author’s Farce: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.